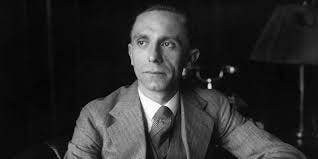

Fritz Lang was a good liar. Even in Hollywood, where he faced Olympic-level competition, Lang’s lies were of podium standard. His biggest lie, the one that still lingers in writing about his career, is that he fled Germany a few hours after Goebbels asked him to become the chief of all German film production. That, of course, meant Nazi-approved production. This was supposed to have happened in March or April of 1933, in the Propaganda Minister’s imposing and cavernous offices on Wilhelmsplatz in Berlin.

Lang was by then world-famous - not just for Metropolis, his dystopian vision of a future in which technology has corrupted the human race - but for M, in which Lang makes us sympathise with a child-killer (Peter Lorre) who’s pursued by a mob. Lang was rich, temperamental and affected (he liked that his monocle scared people); he was used to getting his way, at least when making films. He was less adept at dealing with Nazis.

Lang’s version of his meeting with Goebbels was like a scene from one of his German films. He talked about his steps echoing through the wide halls of the ministry building as he walked to Goebbels’ office; how his whole body perspired as the ‘charming’ Goebbels apologised for having to ban his latest film - The Testament of Dr Mabuse. The minister then stressed how much the Fuhrer had loved Metropolis (1927) and Lang’s epic two-part silent, Die Nibelungen (1922-24). According to Goebbels - as remembered by Lang - Hitler had said: ‘Here is a man who will give us great Nazi films’.

Lang’s maternal grandmother was inconveniently Jewish, but Goebbels reassured the Austrian director. The party decides who is Jewish and who is not, said the Rechsminister. And were you not raised a Catholic in Vienna? And did you not fight for the Motherland in the last war? We can make you an Honorary Aryan, said Goebbels (in Lang’s telling).

Goebbels then proffered the great temptation - would he head up the new agency overseeing all German film production? Great power, great influence, great money - what’s not to like? It was at this point, Lang said, that he realised he had to get out - not tomorrow, but today, on the night train to Paris. He kept glancing at the clock as it ticked past three, then four o’clock. The banks would all be closed; how would he get his money out? Tick tock tick tock… sweat, sweatier, sweatiest. Finally freed from the meeting, Lang rushed home and gathered what cash he had stashed in the house. The amount varied, according to when he told the story: 500 marks, 3000 marks, 5000 marks. He sent his man-servant ahead to buy the train ticket. At the last minute, he boarded the overnight train for Paris, but he was not yet safe. What if they searched him? He stashed wads of money in hiding places on the train. The next morning, he was in Paris. He had escaped - with, at least, some cash.

According to Patrick McGilligan’s forensically detailed biography (Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast, 1997), the director first told this story for publication ten years later, in Hollywood, when he was promoting the first of four anti-Nazi films that would revive his American career. This was 1942 - a few months after Pearl Harbour had forced the Americans into the war. He retold it many times, changing and embellishing the details, until it became part of the lore of Lang.

We now know different. Lang’s own passport survives. It shows he did not finally leave Germany until July 1933, more than three months later, and that he came and went - to Paris, to London, back to Berlin - several times in those months. Goebbels’ ministry diary survives: it does not mention a meeting with Lang in March or April of 1933. This does not destroy the whole fabric of the story, but it does punch a few holes in it. Lang did flee Germany, just not when he said he did; Goebbels probably did offer him the big job, because others recalled Lang asking them whether he should take it. That in itself is damning, because it means he was considering throwing his lot in with the Nazis. The late Pierre Rissient - a friend from much later - told McGilligan that Lang did not make up his mind to leave until he had a new deal in Paris with the already-exiled German Jewish producer, Erich Pommer, who had been the initial producer on Metropolis.

'I never bought the Goebbels story,’ David Overbey told McGilligan. David was an American critic who became a close friend of the director in Los Angeles. ‘For one thing I heard him tell it in greater and greater detail. There were no inconsistencies ever in his telling, but by the time I heard it for the eighteen millionth time, I thought it was a piece of stagecraft - the aria in the opera. The colour of the carpet as he walked into Goebbels’ office would change. It depended on who he was selling it to, and what audience’.

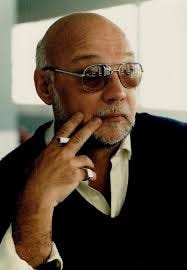

Overbey told me some of these same stories. We became friends at the International Film Festival of India in New Delhi in 1989, after I took over as director of the Sydney Film Festival. David was by then an elder statesmen of the festival world - a senior programmer at Toronto, and one of the selectors for Critics Week at Cannes. He knew everybody. He took me - who knew nobody - under his wing: ‘you must meet this person but don’t trust that one - and never even speak to that one!’ We would meet at various festivals, but always in Berlin in February - not far from where Fritz Lang had met Goebbels.

David Overbey, in characteristic pose, with Gauloises.

In Los Angeles in the late 1960s, David had been an academic and journalist, keen to interview and write about the legends of the industry. Lang was already well into his ‘70s. David used to drive him to various colleges in California, when the director had been booked to speak to film students. The mornings of these visits would usually be taken up with Lang seeing a prostitute. He kept a little black book of phone numbers. Fritz liked a blowjob before lunch, David said, with characteristic mirth. McGilligan confirms the preference: ‘It is less hard work,’ the director liked to say. For whom, one might ask?

The young Lang had a penchant for prostitutes even before he left Vienna, late in 1910. McGilligan writes that they were for him ‘a shrine at which to prostrate oneself and worship.’ That’s an interesting way to put it: it’s clear that Lang had a curious relationship with the many, many women in his life - somewhere between dependance and derision. Did he even like women, I wonder? He was highly sexual. He loved women in the hundreds, one at a time. He loved turning unknown actresses into stars, but that can also be seen as a desire to control. He had affairs with some of the most fabulous women in movies - including Marlene Dietrich, Kay Francis and Miriam Hopkins - but they never lasted long. He was often a beast to those who loved him, like Thea von Harbou and Lily Latté, with whom he had long relationships. He was hugely dependant on them and yet often scathing in public, even as he pursued his latest conquest. He was also a renowned bully on the set, especially of actresses. He tended to toady up to the powerful and punch down at the subordinate, writes McGilligan.

Lang created one of the most fabulous female images in cinema - the robot woman in Metropolis - while torturing the young actress who played her. Maria the robot gets burned at the stake in the film’s climactic scene. Lang insisted on real flames licking the toes of the scantily-clad Brigitte Helm, who was 19 and new to movies. Inevitably, the flames ignited her dress at one point, and had to be quickly extinguished. Lang’s crews were often appalled at his treatment of women, but he also tortured his male actors. Herr Lang was an equal opportunity bastard, in that sense. A megalo-mytho-maniac, of sorts. No wonder Hitler liked him.

Lang was also a political neophyte, at least in Berlin. He was wary of Nazi ideology, but had little ideology of his own, at least in political terms - and to be fair, nobody really knew in 1933 how far Nazism would go. On the other hand, many of the Jews in the film business had already fled. Fritz Lang was Jewish enough to know that he would face trouble if he stayed. He made one film in Paris with Erich Pommer - Liliom - then sailed for America with David O Selznick, in the middle of 1934. Lang was now under contract to MGM, the first of many studios at which he would build and then burn his bridges.

Brian Donlevy hides from you-know-who in Hangmen Also Die!

By the time he came to make the four anti-Nazi films - Man Hunt (1941), Hangmen Also Die! (1943), Ministry of Fear (1944) and Cloak and Dagger (1946) - Fritz Lang had become a fervent anti-Fascist and a dabbler in leftist causes. That made him suspect for the powerful right-wing forces in America. In 1940, his name had appeared on a list of secret Communist sympathisers, who were said to be trying to further the Russian cause in Hollywood. Bogart and Cagney were on the same list, compiled by John L Leech, a functionary of the American Communist Party, and shown to a grand jury in Los Angeles. Lang immediately put out a strong denial: ‘A few years ago I was accused of being a Nazi… As a fugitive from Nazi Germany, the charge was ridiculous. This charge is even more ridiculous. I hate Hitler - I hate Stalin - I hate all dictators and dictatorships!’

The commie hit-list was a harbinger of dark things to come in Hollywood, but the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour interrupted the witch-hunt. Hollywood now went to war. To a large extent, studio production became an arm of American propaganda. Studio heads liaised directly with the government’s new Office of War Information about the types of pictures the country needed. This became comical at times: even Tarzan went to war, in Tarzan Triumphs (RKO, 1942). Joe E Brown foiled Nazi agents in a bowling alley in The Daring Young Man (Columbia, 1942). Cartoons, musicals and gangster movies all put on the uniform. Many actors and directors actually put on the uniform, enlisting to fight. Not Lang. In 1942, he was 51. Where exactly would a Teutonic control freak with a monocle fit into this man’s army?

Lang’s career was in the doldrums before he made Man Hunt - a fairly clumsy thriller about an English big game hunter on the run in England from Nazi agents. He had been out of work for almost two years after You and Me (1938) - a quasi-musical that laid a giant egg at Paramount. In 1940, Zanuck hired him to direct The Return of Frank James, a western; then another, Western Union. Having alienated half of Hollywood since his arrival in 1934, Lang was now on his best behaviour, keen to show he could direct a commercial script on time and on budget. The war gave him a renewed purpose. Being anti-Fascist was back in fashion. Lang was keen to play his part. It would be foolish to think the attempts to label him as both a Nazi and a Communist had no effect on him. Emigrés were vulnerable, even in Hollywood. How better to prove his loyalty to America than to make pictures that showed what the Nazis were really like?

Hangmen Also Die! is perhaps the best of Lang’s anti-Nazi movies, but whether it is effective as propaganda is debatable. It’s blunt, gripping and hard to misconstrue: the Nazis are awfully nasty. They must be defeated at all costs. But therein lies a problem: audiences don’t generally like being lectured. ‘The easiest way to inject a propaganda idea into most people’s minds,’ said the OWI’s first director, Elmer Davis, ‘is to let it go in through the medium of an entertainment picture when they do not realise they are being propagandised.’ Lang deals with this by making propaganda a part of the film’s subject.

The assassination of Reinhard Heydrich in Prague in May 1942 was worldwide news. Heydrich was then the ‘Protector of Bohemia and Moravia’, the former Czechoslovak territories annexed by Hitler in 1939. Heydrich was extremely senior, and just as brutal. One of his nicknames was ’The Hangman’. Hitler sent him to Prague to crack down on the rebellious population. Czech workers were deliberately slowing military production. As the film opens, in a grand 18th century salon in the royal palace, Nazi officials upbraid the Czech leaders for the ‘slow-down’ propaganda appearing in the Skoda factories. We see cartoon leaflets urging workers to obstruct the work. A Czech official explains, carefully and timidly, that it might help if the Nazis paid the workers enough to afford food. A Nazi officer then sweeps into the room, jodhpurs quivering, and announces: ‘Ihre exzellenzen, der Reichs-potato’. At least that’s what it sounds like. It may well have been one of Fritz’s little jokes, to substitute ‘potato’ for ‘protektor’. The film at this point rings with dark humour at the Nazi’s expense.

Heydrich then appears in full regalia. He is played by the impressively named Hans Heinrich von Twardovski, a prominent silent film actor - and gay man - who had fled Germany before Lang. He strolls in with a malevolent half-smile animating his thin, vulpine face. He looks like a vampire on day release. Heydrich is enjoying the fear in the room, symbolised by the sea of outstretched right arms. He stops in front of a fat man with an eye-patch, a Czech general who has saluted the old-fashioned way, with fingers to the temple, rather than the stiff arm. Heydrich drops his leather-bound cane at the man’s feet, glaring until the general picks it up and hands it back to the sneering Reichs-potato.

Actually, you don’t need me to describe the scene, as the full film is available on Youtube. You can watch it below*. Be my guest - then come back here for the rest of this scintillating commentary. I guarantee there is a point to all this meandering.

OK, from here on, I will assume you have watched some or all of Hangmen Also Die! There will be spoilers.

A distinguishing feature of that opening scene is Lang’s dark humour, from the self-satirising portrait of Hitler in trench-coat, right hand cocked on hip, to the way that Heydrich returns the Hitler salute, with the merest wave. That says ‘I can do the salute however I like but you better do it right or I’ll have you shot’.

The film quickly becomes more threatening, which is really the point. This is a study of what people do under pressure - and as that, it remains remarkably timely and effective. Lang is interested in how ordinary people respond to intimidation, a theme that never gets old. The people of Prague know the Nazis don’t issue idle threats: they will do what they say. In this case, they take hostages, demanding that the people give up the assassin of Heydrich. They soon start shooting those hostages. Some of the population call on the assassin to hand himself in.

The plot is exquisitely savage. Pretty young Masha Novotny (Anna Lee), sees one of her countrymen being chased through the streets by Nazi soldiers. She is not part of the Resistance, but she is a proud Czech. She misdirects the soldiers, allowing the stranger to escape. That action will cost her dearly.

Lang does not show the attack on Heydrich. No-one in Hollywood yet knew the real story anyway but that’s probably not the reason. He does it so that we do not have more information than poor Masha. She sees a man being chased. This man, played by Brian Donlevy, needs her help. She might have withheld that if she knew that he had just shot Heydrich. (In fact, Heydrich’s killers were two exiled Czech army officers trained in England by the SOE - the Special Operations Executive).

Her actions brings the fugitive Donlevy character into her home, where her father, Professor Novotny, sees that this man is likely to be the assassin. The professor is played by Walter Brennan, a surprising but inspired bit of casting. Brennan was well-known to American audiences as a colourful figure from westerns, often portraying gabby hayseeds.

Here he is immensely dignified and brave, a man of towering integrity. Brennan gives the most soulful performance in the film, in powerful contrast to the gangster Nazis.

Lang then gives us a range of others who stand at different points on the spectrum of bravery - from Resistance fighters to the stoic old vegetable seller, Mrs Dvorak (Sarah Padden), who dies after a Gestapo beating. By this point, the Nazis are no longer figures of fun: Lang makes us see their true colours, the unrestrained ruthlessness at the heart of their project. He also shows that there is also a spectrum of treachery among the Czechs: the Nazis don’t have to work hard to find collaborators. The brewer Czaka has infiltrated the resistance in order to betray them to the Gestapo. Casting Gene Lockhart - usually a jovial comedic presence - is another clever stroke. Lockhart uses his jolly image as cover with the audience, as well as the people of Prague.

Gene Lockhart - looking worried.

Lang took great pains in building a plot and this one keeps getting deeper, as the reprisals start. In fact, those reprisals were much worse than we see - perhaps as many as 5000 executions. We don’t know how much Lang knew of the real reprisals, but it wasn’t hard to guess. We do know now that some of the Czech leaders tried to stop the plot to kill Heydrich, fearing that the price would be too high.

You will have noticed a screen credit for story by ‘Bert Brecht’. The famous playwright had arrived in Hollywood July 1941, as part of a new tide of German exiles. Lang welcomed him warmly. They began discussing idea. As soon as they heard of the assassination of Heydrich, they started work on Hangmen Also Die! The process quickly degenerated into acrimony, especially when veteran writer John Wexley joined the team. Wexley eventually claimed sole credit; after arbitration, Brecht had to accept a story credit. The whole process confirmed his distaste for American capitalism. It is difficult now to know how much Brecht contributed, but there are surely some familiar echoes, in the sympathetic portrayal of workers and Resistance fighters.

Who really cares about this film now, more than 80 years later? Let me offer a reason. Hangmen Also Die! is about civilian resistance to intimidation and it’s not like that has gone away. Indeed, I can’t think of a time when crude intimidation has become so much a part of the daily news. I am not just talking about the tariff-monster. Those around him are like cutouts from Lang’s film: toadies, bullies, liars and wreckers in expensive suits. One of them even showed us his best Nazi salute at the inauguration.

Lang himself was tempted by Goebbels, before he saw the blood red future - and Lang was rich, famous and powerful. Hollywood - that bastion of liberalism - threw everything at Trump last year before the US election. It didn’t work. The movie mavens then pulled in their heads. In January, they were conspicuous in their lack of support for The Apprentice - the film that dramatises Trump’s formative years. They were right to be afraid: vengeance is Trump’s favourite sport, after golf. The roundups and deportations of the poor and dispossessed have already started. Who’s next? Remember that famous poem by the German pastor, Martin Niemöller?

First they came for the Communists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Communist

Then they came for the Socialists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Socialist

Then they came for the trade unionists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a trade unionist

Then they came for the Jews

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Jew

Then they came for me

And there was no one left

To speak out for me

Fritz Lang wasn’t a communist either. Nor a Nazi. He may have been a bastard and a bully but he was also a perceptive observer of the darkness in the human condition. Hangmen Also Die! has many of his bone-chilling touches, especially in the concluding scenes, which reinforce the callousness of the Nazis, laughing as an old man is gunned down on the steps of a church. The fact that this is Czaka the traitor, killed by Gestapo thugs, is pure Lang. We almost feel sorry for Czaka. Lang then cuts to the machine-gunning of the hostages, including the professor. As mourners visit the mass graves of the dead, we hear a stirring song, proclaiming ‘No surrender’. That had been the original idea for a title. I don’t know whether the film was effective as war-time propaganda - but I do think that the depiction of the dark mechanisms of tyranny still packs a punch.

…

*All of these films are available free on Youtube, except for Ministry of Fear, which is available on The Internet Archive.

Very informative, thanks Paul x

Very enjoyable and informative. The Goebbels 'story' was new to me.