If Liberty Valance ran for president...

Revisiting John Ford's classic film about American politics and the Old West

In 2003, when the American Film Institute drew up a list of the greatest movie heroes and villains, Liberty Valance did not even make the top 50 bad guys. A gross injustice, I say. If Nurse Ratched and Hal 9000 made the grade, why not the man who personified everything that was wrong in the Old West - at least ‘south of the Picketwire’ - and may I say, some of what’s wrong now, 'east of the Potomac’.

John Ford made The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance on the Paramount lot in late 1961. He was 67 years old - the same age I am now - and one of the most famous directors in the world, with a career that already spanned almost 50 years. He seems to have had a lot to get off his chest. John Kennedy was president and the times were soon to be changin’. Otto Preminger had defied the McCarthy witch-hunterss in January 1960 when he announced that he had hired former communist Dalton Trumbo to adapt the screenplay for Exodus. In August, Kirk Douglas announced that he too had hired Trumbo to rewrite Spartacus two years earlier - albeit in secret. The era of the blacklist was crumbling, but Ford was never one to blow with the wind. Ornery could have been his middle name.

Ford scholar Tag Gallagher has called Liberty Valance ‘an old man’s movie’. I think that’s right, but in a good way. It’s a moral lesson drenched in old-time American values like rectitude, honour, loyalty and generosity, all of which are threatened by a hoodlum called Liberty, played by Lee Marvin. Liberty Valance, the man, is to goodness what the current American president is to modesty. Liberty would happily drag any of those American values off its horse and pistol-whip it. He’s bad to the bone. In Mel Brooks’s Blazing Saddles, made 12 years later, Harvey Korman spits out a fabulous list of all the bad guys he wants assembled - ‘rustlers, cut-throats, murderers, bounty hunters, desperadoes, mugs, pugs, thugs, nitwits, half-wits, dim-wits, vipers, snipers, conmen, Indian agents, Mexican bandits (deep breath); muggers, buggerers, bushwhackers, hornswagglers, horse thieves, bull dikes, train robbers, bank robbers, ass-kickers, bush-kickers, and METHODISTS!’ Liberty Valance may be missing but he’d qualify for most of the job descriptions. At the time, we laughed because Mel Brooks’s list seemed so outlandish. Now it sounds like a description of Donald J Voldamort’s Cabinet.

Ford didn’t much care for the political witch-hunts of the 1950s, but he was hardly a political radical. His politics were deeply sentimental, mixed up with patriotism and romanticism, a longing for the past and fear for the future. At times he was a conservative Republican; at other times, a liberal Democrat. His idealism was only matched by his cynicism - which may explain why he drank so much. Both sides of his nature are evident in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, a film that celebrates the Old West even as it tears it down. Ford examines the mythology that he did more than any other director to create, and finds it wanting. In that sense the film is both a civics lesson and a form of self-criticism. Ford the iconoclast loved the rough-hewn values of American democracy, where drinkin’ and fightin’ and rowdy conventions provided a pageant of human behaviour. Ford the moralist hated the lies and corruption behind that political process. That is the subject of the movie - how a legend produced a big man, and the legend was a lie.

Watching it again, in these dark times, it’s hard not to notice the ambiguity of Ford’s view of America - and how far America has come from the ideals of that time. At its most benign, Liberty Valance is a film about the civilising aspects of law and order. The man who thinks he shot Liberty Valance is a towering example of a good man. That may by why Ford cast Jimmy Stewart, whose American goodness was only topped by Rin Tin Tin.

Stewart’s character Ransom (‘Ranse’) Stoddard represents the coming of order, and thus, the passing of the rowdy vitality of the Old West. John Wayne’s character Tom Doniphon represents that vitality, but with a moral backbone. Lee Marvin, as Liberty, dispenses with the backbone. He’s just low-down outlaw scum, a man who enjoys hurting people and has trouble controlling that urge - a psychopath. When Ford made the movie, Kennedy was asking Americans to heed their better angels, to ‘ask not what your country can do for you’ etcetera. Here was a movie that showed, at least on a surface reading, that good had defeated evil in the making of America. Or had it?

It’s hard to ignore the attractiveness of Lee Marvin’s depiction of a bad man. His cruelty is part of the spectacle of the movie. It’s implacable, but tinged with a devilish kind of humour. Liberty is stylish, dangerous and very, very sexy in Lee Marvin’s performance - and he gets to wear the best clothes, courtesy of Edith Head’s costuming. You can’t take your eyes off him. Goodness may be its own reward, but badness is having more fun, it seems.

It seems odd to say it, but I think Liberty Valance is one of Ford’s most autobiographical films. It’s partly about the attraction of violence as a form of freedom. Perhaps that’s why the character’s name is Liberty (yes, I know, Ford did not name him - the original 1953 short story was by Montana-based writer Dorothy M Johnson). Ford looks at cruelty here with the eye of one who knows its contours: he was capable of great cruelty himself. He loved to terrorise and humiliate his stock company of actors, even the ones he loved most, like Wayne and Harry Carey Junior. He is reputed to have ridden Wayne hard on this movie, taunting him with his lack of service in the Second World War and his failure as a college athlete. Ford was a bully, as so many of the great film directors were, in an era when they could largely get away with it. I think Ford was attracted to the no-holds-barred ferocity of Liberty Valance.

Stewart plays a man of peace, an eastern lawyer who refuses to pick up a gun, even after he is repeatedly assaulted and humiliated by Valance. Ransom Stoddard is a man of virtue in a place where no-one has much use for it. That struggle is foundational in the Western, as it was foundational in American life. Ford was born at the end of the 19th century, when the west was already won - and lost. Buffalo Bill was riding in a tent show as early as 1882. Ford came to Hollywood in 1914, where his older brother was already a successful actor, and ‘Jack Ford’ was soon directing short westerns. The aging Wyatt Earp was a frequent visitor to John Ford’s sets in the silent era. In that sense, Ford had primary sources for some of his stories. Henry Fonda would eventually play a sanitised version of Earp in My Darling Clementine, one of Ford’s most romantic films.

The western was in decline when Ford made Liberty Valance. The Second World War had broken its spell. American power had never been greater, but the western no longer explained the world, as it had become, to Americans. Ford’s westerns of the late 1940’s are some of his best but they have an elegaic tone - as in his cavalry trilogy (Fort Apache, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Rio Grande). The man who helped to invent the western was now mourning it. From 1950 to 1959, Ford largely abandoned the genre, except for The Searchers (1956), perhaps his most famous and ambiguous film - a paean to the white pioneering families of the west and a stunning indictment of their racism. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is a sort of companion piece, a summary of Ford’s disillusion with the illusions of the Old West, in which a man builds his whole life on a lie.

The film is told largely in flashback, at night, in the town of Shinbone. We don’t know where this is, except that it is out west and ‘south of the Picketwire’. The Picketwire is a real river in southern Colorado, apparently a mispronunciation of ‘Purgatoire’. Ford never names the territory, except to make it clear that it is a territory wanting to become a state. In fact, that is part of the civics lesson - a controversial part, as it adds a 20-minute political rally at the end that some critics found unnecessary. Not me. I say that last 20 minutes ties Ford’s political agenda together the way the rug tied the room together in The Big Lebowski.

Most of Ford’s films since the war had been in colour; not this one. Except for a couple of scenes of the railroad, and the ranch house that John Wayne is extending in the hope of attracting a bride, the film takes place in rooms in the town, in a series of set pieces. Ford was famous for his use of landscapes, specifically those of Monument Valley. There are no great vistas in Liberty Valance. It’s a chamber-piece, a western with almost no horses. Who’d have thought?

Ford simply returns to the basics of story: two protagonists, one antagonist and a mystery to solve. He takes the western indoors and after-hours here, to where men eat and drink, read newspapers, talk shit, engage in politics and flirt with girls. As so often with Ford, a young woman is at the heart of the meaning.

Vera Miles - Miss Kansas of 1948 - is Hallie, Tom Doniphon’s sweetheart. She is half of the film’s conscience, its heart and soul. She is also the ‘territory’ that John Wayne and Jimmy Stewart will fight over, in a purely symbolic way. Hallie is uneducated, but full of life. She is kind, hard-working, funny and unsure of her own intelligence, because she can’t read. Stoddard starts a class to teach her to read and half the town joins in. Ranse schools them about the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence and the democratic system. At the back of the class, like a sentinel, stands Pompey, the only black man in the film - and the other half of the film’s conscience. Woody Strode had starred in Sergeant Rutledge for Ford two years earlier, a role that gave him immense exposure. Here he plays John Wayne’s hired hand but he’s also his friend, even if Wayne call him ‘my boy Pompey’. Strode’s presence in a number of scenes changes the meaning of those scenes. Civil rights had been a topic for Ford long before the Kennedy administration came to power. At the political convention late in the film, Pompey sits on the stoop outside the door, looking baleful. He doesn’t say a word. Ford placed him there for a reason, to show that Pompey is just a bystander to this great new democratic process. He can’t go inside and vote.

Tom Doniphon watches uneasily as Hallie learns to read. He accuses the lawyer of trying to take her away from him. Stoddard calls that a damned lie. He doesn’t know yet that he’s in love with Hallie too. It’s a love triangle, in that sense, but a rather beautiful one because it’s so recessive. Ford rarely brings it to the forefront: it happens in the shadow of a real and present danger - the rampant threat of Liberty Valance, a man who knows no higher emotion than ‘I want…’

Valance is a bully’s bully - ‘a no-good gun-packing murdering thief’, as Jimmy Stewart declares after his first beating. We’re never told how Valance got that way: it doesn’t matter to Ford. Valance is the product of a place in which brutality is a currency. It has corrupted the population of Shinbone; everyone puts up with it, out of fear. Stoddard can’t understand how the people have become so pliant. John Wayne is the only one who doesn’t fear Valance. In fact, he’s itching to take him on.

Violence erupts in the first scene, as Valance and his pals hold up the stage coach on which Stoddard is travelling. Valance becomes enraged when he discover’s law books in Stoddard’s luggage. He tears out pages and thrashes him with them. ‘I’ll teach you law - western law,’ he cries. Stoddard is cowering on the ground, off camera. Ford only shows us Valance’s rage, as he belts him with a short-tailed whip attached to a long leather bludgeon - a fairly obvious sexual symbol. Lee Van Cleef has to haul Valance off before he kills the lawyer. The reason for Valance’s anger is clear: Stoddard is educated.

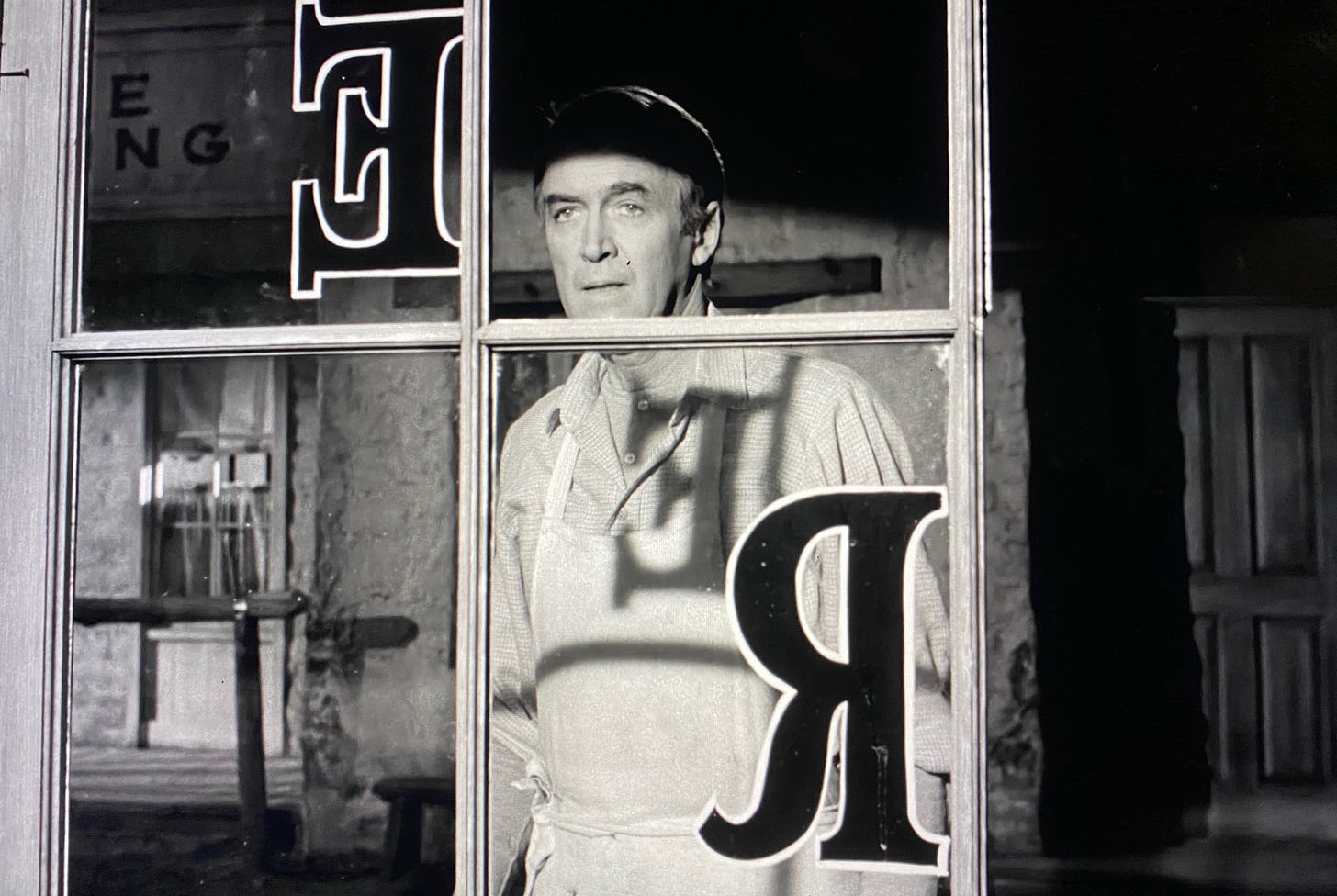

Social life in Shinbone revolves around a saloon and a cafe. Unusually for Ford, more scenes take place in the cafe than the saloon. Peter and Nora Ericson (John Qualen and Jeannette Nolan) are Swedish immigrants who serve steaks that would kill a vegetarian. Hallie is their waitress. They are kind and gentle folk - exceedingly proud of their new country and their citizenship. Ford’s family were Irish immigrants: he makes a point of valourising Peter and Nora. Their cafe is the film’s hearth - a rowdy centre of community, where Ford gets to observe the highs and lows of humanity. Stoddard becomes part of the Ericson’s cheerful circle of affection. With no money, he pays his way by washing dishes and bussing plates. He even wears an apron, a picture of gelded masculinity. John Wayne makes fun of him until Liberty Valance swaggers in, calls Ranse a ‘waitress’, then trips him up as he carries a huge steak to Doniphon. Bad move to interfere with another man’s beef.

The film is couched as a long flashback - Stoddard’s recollection of events 30 years earlier. The opening scenes, with Stoddard returning by train to Shinbone, are set around 1908. Stoddard is now a distinguished US senator who looks like becoming the next Vice-President. He has come for a funeral. The editor of the local paper demands an interview. That’s when we learn that the funeral is for Tom Doniphon. Hallie is now Mrs Stoddard, so we know from the start who won the fight for her hand. At the funeral parlour, Pompey sits in vigil next to the coffin.

According to Ford, Doniphon is the film’s lead character, not Stoddard. That’s maybe a line ball. Part of what makes the film so watchable is the competition between three stars at the height of their powers, working with a master story-teller. Ford is one of the most gifted directors in the history of the medium and he had lost none of his edge. The high contrast black and white is ravishing. Ford said it was an artistic choice; the cinematographer William H Clothier said the studio just wanted to save money. We can be grateful that they did: there are few films that use the lack of colour so well. Ford also said that the climactic gunfight, where we learn who did shoot Valance, would not have worked in colour - an intriguing comment. Why not? We need to look at a still from the big moment to see why. It’s a spoiler but then, if you haven’t already seen the film, you’ve probably not got this far in my brilliant appreciation of the film’s riches (irony alert).

Look at the lighting in the shot below as Stewart walks to the showdown against Valance. The rim light on his head and shoulders is almost pure white, emphasising his loneliness in this moment. The light catches the gang in the Mexican cantina, cowering behind the door, suspended by the tension. They are us, the audience, who cannot look away. Now imagine all this in colour - all the drama and clarity becomes muddied. In black and white Ford can direct our eye wherever he wants - the hanging lamp, the election hoarding, the gun in Stewart’s hand. Colour would only confuse things.

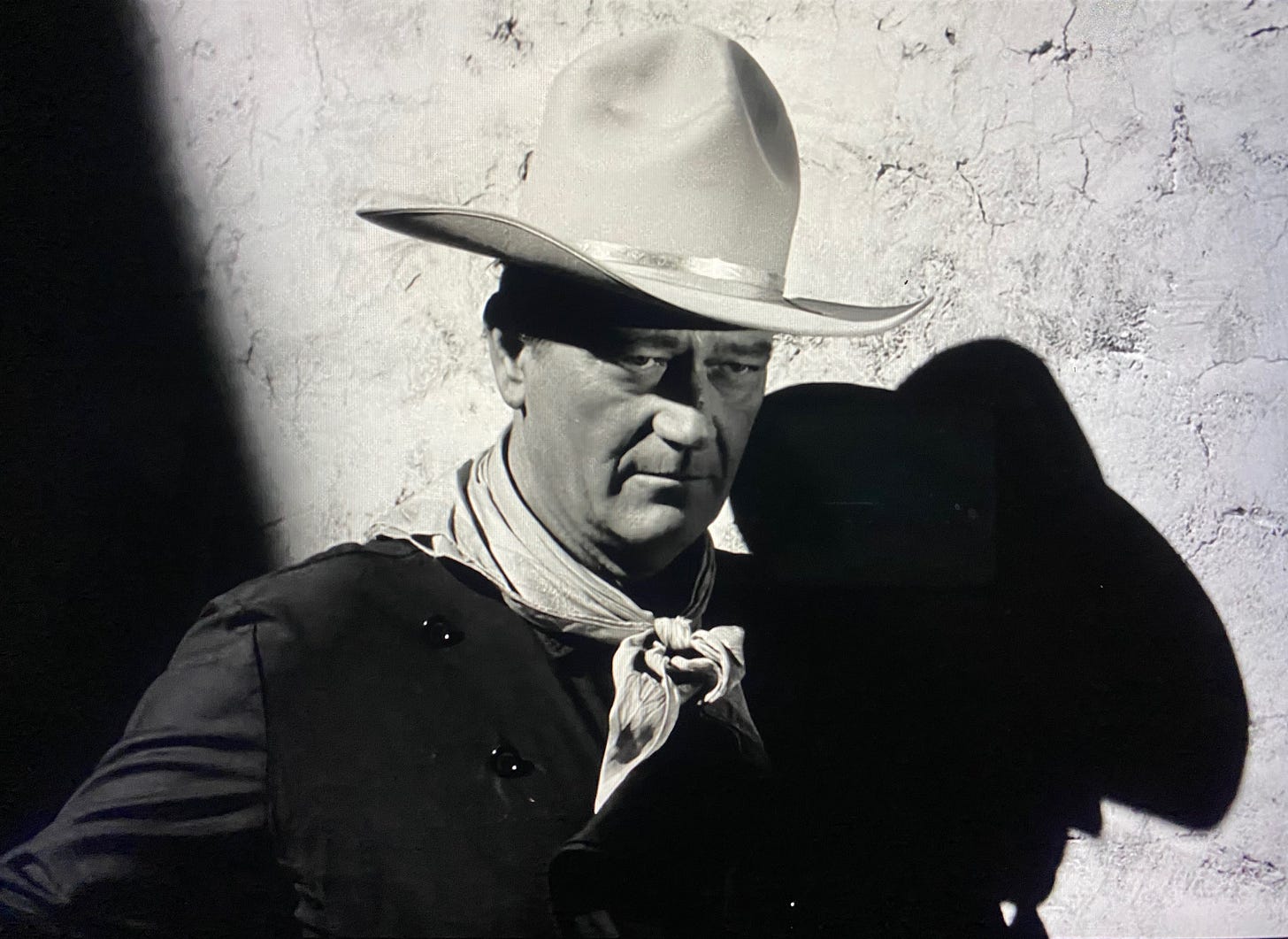

Monochrome also gives contour to the faces, which allows for more subtle performances. Look at this shot of John Wayne, just after the shot above. He is watching from the wings - and the shadows are dramatically significant.

There are two Tom Doniphons here. One is the good man in the light, the other is the righteous killer in the dark shadow who’s looking forward to tangling with Valance. That’s who Tom is looking at here, just before the shooting starts. The light bisects Tom’s body, but there is enough light on his face to see the hatred in his eyes. He has been spoiling for this fight since the restaurant scene, and probably before. He doesn’t like bullies. Ford uses light to amplify meaning here. Colour photography would not have had the same impact. There would have been detail in the shadows rather than full black. If the studio really did force him to use black and white to save money, he made the most of it.

The Woody Strode character Pompey is one of two major characters who are not in the original Dorothy M Johnson story. The other is the drunken newspaper editor of the Shinbone Star, Dutton Peabody, played by Edmond O’Brien. Both tell us something about what Ford was trying to say. I think Peabody is John Ford’s jocular version of a self-portrait: a hopeless drunk with a good education, a romantic spirit and an acute sense of morality. His newspaper writing is vivid and spurs Stoddard to take up the cause of the townsfolk, against the big ranchers. They oppose statehood. They don’t want fenced farms and the law. For them, the lawless open range is a freer and more lucrative place of business. They hire Valance as their enforcer, which takes the film deeper into politics, where it has been heading all along. Valance is now more than a simple hoodlum; he is the vicious tool of big money. One of his first targets is Peabody, whom he beats to a bloody pulp as his goons destroy the newspaper office. So much for a free press. Valance then tries to intimidate a town meeting into voting for him as one of the delegates to a coming convention on statehood. Liberty never makes it to the convention. The injuring of Peabody incenses the once-peaceful Stoddard. He picks up a gun.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is thus a somewhat contradictory film about might versus right, education and the law against gangsterism and intimidation. However high-minded, it’s still resolved with a gun - two guns in fact. From 63 years later, it has lost none of its prescience and power - in fact, I think it has become more relevant to our times.

Valance targeted the mechanisms of a free society and the democratic process - first he shut down the press, then he intimidated the voters with threats of violence. He didn’t just ignore the law, he ripped up its pages and stomped on them. He was a bully, a braggart, a showoff and yet, a bit of a coward when faced with the mighty John Wayne. Valance did not appeal to anyone’s higher nature, only their fears. Sound like anyone we know?

When Ford made the film, Valance represented an ugly negative, the worst that the culture could produce. His values were despicable. One year after the film came out, John Kennedy was dead in circumstances that echoed the mystery of the film: were there two shooters or one? The American war in Vietnam was escalating. American idealism would be torn apart in that decade, bringing Richard Nixon to the presidency. John Ford even voted for him. In that sense, perhaps, nobody shot Liberty Valance. The rough justice of the film was just a playground illusion. The most famous line in the film comes near the end when the 1908 newspaper editor (Carlton Young) declines to print the story that the elderly Ranse Stoddard has told him, even thought it’s true. ‘When the legend becomes fact, print the legend,’ the editor says. Ranse wants to admit that his whole career is based on a lie, but nobody wants to know. I can almost hear the chuckles coming from the West Wing late at night: ‘What a loser’.

This might get Jen watching Westerns…

Loved this Paul. Entices me to take a look.