Sunday, March 2

Popeye Doyle is gone. As I write, the airwaves are full of speculation about the horrible details of Gene Hackman’s death, rather than the man’s stellar career and achievements. In death, he has become a tabloid frenzy; in life, he was just one of the best who ever stepped in front of a movie camera. I loved him on screen. Seeing him and his wife torn apart as a two-minute news item breaks my heart - even if I am and always will be a newspaper guy.

He was never the biggest star, but he was unusual in that he was a character actor who became a star. The bigger male stars, like Clint Eastwood and Warren Beatty and Richard Gere, all wanted to work with him, because he could carry more than his load. Whoever he played, he would be reliable and real, and he could enliven any scene. The public knew that too: he guaranteed a certain level of quality. Even if the movie was bad, Hackman would be good.

When I started reviewing movies in 1984 for The Sydney Morning Herald, Clint Eastwood was the reigning urban tough guy (west), but Hackman was the urban tough guy (east). The French Connection, set in New York, came out in October 1971 and made him a star. Dirty Harry, set in San Francisco, came out two months later in December, and had a similar effect on Eastwood’s career. It was the Era of the Lawless Cop, although the two actors had very different styles - and Hackman was always a committed Democrat, while Eastwood was a noted Republican.

Hackman was heir to the crown of Jimmy Cagney - not just tough, but mean. Popeye Doyle was a sonovabitch, a New York cop of the worst kind. ‘Never trust a nigger,’ he said to Roy Scheider in that movie, after they had beaten a black dealer to a pulp in an alley. I rewatched the film last night here in Australia and the line is no longer there: someone has quietly edited it for modern times, an act of corporate vandalism. Hackman hated saying the line himself, but said later that he knew it was right for the character. He also told interviewers that he disliked the violence of his role - so much so that he went to the director Billy Friedkin on the second day of shooting and asked to be replaced. Friedkin refused, probably because he knew that Hackman had more anger in him than any actor in the business. His whole career was built on anger and discipline - the anger set the fire, the discipline controlled the burn.

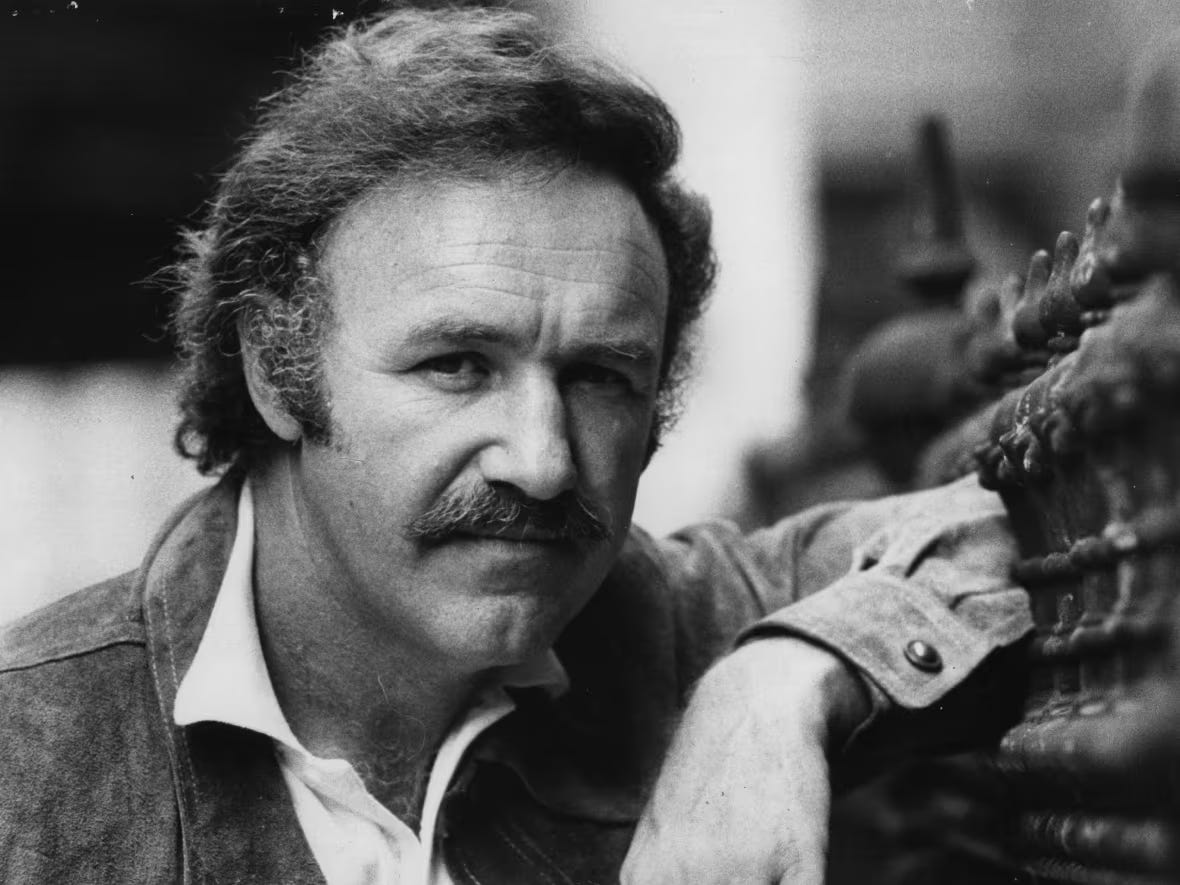

Eugene Allen Hackman wasn’t a tough guy like Bruce Willis or John Wayne, where the violence was mostly righteous or cartoonish, and built on their perfection as physical specimens. Hackman didn’t look like a matinee idol. He looked more like your car mechanic, with hooded eyes and that enormous forehead exposed by a receding hairline (and what hair - like steel wool on a billiard ball!). Great movie stars generally have beautiful eyes and directors make sure we see them. Hackman had piercing little eyes that would disappear with his sinister smile - and you could barely see what colour they were because his swollen brows kept the light from hitting them. An oil painting, he wasn’t.

What he was, was the guy you’d fear to be around if someone pissed him off - hard as nails and meaner than a junkyard dog. In movie after movie, the anger blazed. No-one erupted better. He was forever shouting in big films of the 70’s and 80’s - like The Poseidon Adventure, where he played a preacher trying to save the survivors of an upturned ship. Much later, he would underplay the aggression, whispering a line so that it would curdle your blood. In Eastwood’s Unforgiven, playing the sadistic sheriff Little Bill, Hackman horsewhips Morgan Freeman in the jailhouse cells. Freeman is tied to the bars like a runaway slave. Hackman approaches from behind, putting his face next to Freeman’s ear, his chin on Freeman’s naked arm. In a very quiet and intimate voice, he tells him he’s going to hurt him real bad. Hackman does it with a startling look of sorrow on his face, like he pities this man he’s about to torture.

Little Bill was one of the best roles of his career, partly because Bill thought he was a good guy. We see him beat three men almost to death on screen - and one of them does die - but Bill was just keeping the scum off the streets. This was the great mixing of the streams - west and east together, with Eastwood as a man trying to leave killing behind, and Hackman as a man who has found that a badge allows him to kill at will.

The role earned Hackman his second Oscar. He had won best actor for The French Connection; this time, he won best supporting actor, but it was the dominant role in the movie. Eastwood had to persuade him to accept the job. Hackman was avoiding violent roles - apparently after his daughters asked him to. Eastwood convinced him that the film was about the cost of violence for men who use it - which was true. It’s still a great movie on that theme.

Hackman could never outrun his association with violence. It was his forte. He had risen on the tide of violent movies in the 1960’s. His performance as Buck Barrow, brother of Clyde Barrow in Bonnie and Clyde (1967) showed that he had honed his technique in the decade since he joined the Pasadena Playhouse in 1956. He had done his share of waiting tables in New York, along with his room-mates Dustin Hoffman and Robert Duvall. Hackman had also had more life experience than many of his generation. In 1946, aged 16, he lied about his age to join the US Marines. He was posted to China, where the Chinese Revolution was still playing out, and then Hawaii. His Marine Corps mugshot shows a face full of attitude and aggression - and perhaps a few bruises. Some of that may have come from his parent’s breakup when he was 13. His father simply waved at his son as he drove away, abandoning the family.

Hackman (born 1930, in San Bernardino, California) claimed to have known by the age of ten that he wanted to be an actor. He said that he had loved the tough guys in movies, particularly Cagney. No surprises there, nor was that exceptional for an American boy growing up in the Depression. A number of acting teachers told him he’d never amount to anything - which is curious. What could they not see that we could all see later? The rejections just made him more determined.

Hackman has always been called an ‘everyman’, as if that explains his appeal. I see the point, but there is more to it. He was not a pretty boy like Redford or McQueen, but he wasn’t Ernest Borgnine either. He could be very attractive, depending on the character, because of his firm jaw and direct gaze - and because of that marvellously supple voice, which could go from honey to chainsaw in a moment. His smile was perhaps the most dangerous weapon in Hollywood for a time: it came out when he was at his meanest, about to kill somebody or beat the shit out of them. It was a cold smile, derisive and cruel. It could be very effective in comedy: Lex Luthor was a comedian in his hands, as well as the greatest criminal mind of his time.

The public loved him in Superman and its sequels, but Hackman did not. He so disliked his performance, he said, that he gave up acting for a while. He could afford to, given what they paid him, but he was also somewhat sanguine about bubblegum movies. He had always been serious about his art, and Lex Luthor seemed to offend his self-image. Hackman had also developed a reputation for being difficult when he was not happy in a picture - which was often, around that time. He said later that he decided to lighten up. He played Luthor again in two sequels. A man’s gotta eat.

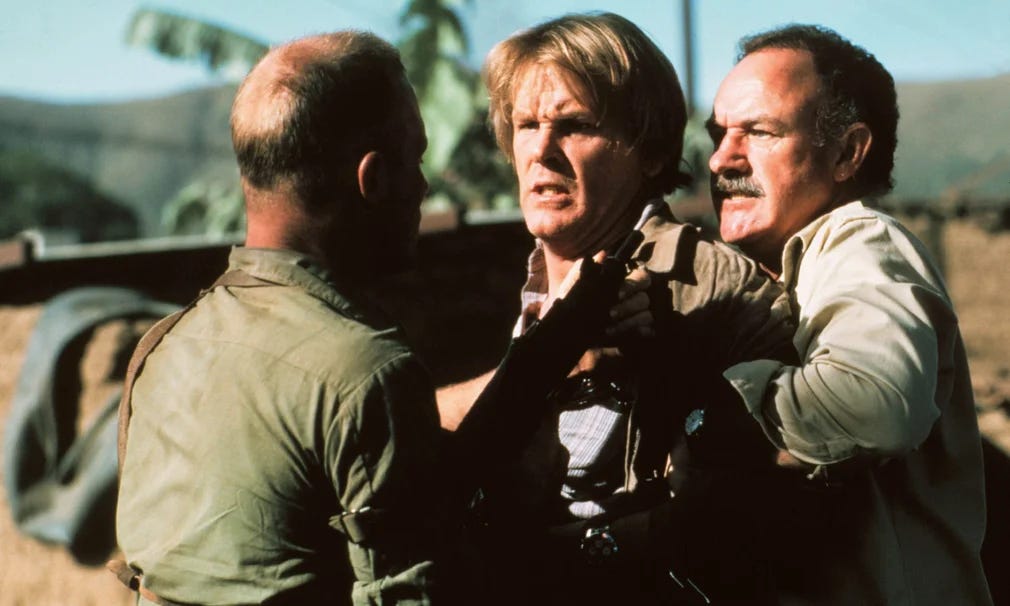

I loved him in most of the films above, but there were so many more. Until 2004, when he quit films, he never stopped working. The less obvious gems would include the ski coach he played in Downhill Racer in 1969 and the basketball coach he played in Hoosiers (1986, aka Best Shot on imdb). In Under Fire in 1983, he and Joanna Cassidy were seasoned war correspondents in Africa, then Nicaragua. They were also married, albeit loosely. Nick Nolte, as a photographer, is also in love with her.

The movie puts Hackman in the support role, at a time when he might easily have said no. It’s also the only film I can recall in which he plays the piano and sings. (I read that there were two Steinway grands in the house in Santa Fe - presumably one for his wife Betsy Arakawa, a classical pianist, and one for Gene…)

It was rare for Hackman to do romance, but he often played a man brought crashing to earth by love. In The Firm, based on the John Grisham novel, he was a corrupt lawyer who regrets the man he has become, especially when he falls for a good woman (Jeanne Tripplehorn playing Tom Cruise’s wife). In The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), he played a dying man trying to rekindle his broken family relationships. Sometimes, he played men for whom violence and sex were entwined: he was a politician in both No Way Out (1987) and Absolute Power (Eastwood again, 1997) who kills a lover and then tries to cover it up. Both were chilling portraits of power.

It’s hard to choose a favourite among his roles. He’s incredibly concentrated as Popeye Doyle, a rocket-fueled demon fighting the drug importing French smoothie, played by Fernando Rey. He was good in so many thrillers, especially those of a political bent - like The Package (1989) and Enemy of the State (1998). He was hilarious in Get Shorty (1995) as a B-movie director. And there was the towering achievement of Little Bill in Unforgiven, a role that demonstrates Hackman at full power and intelligence. ‘Intense and instinctive’, as Eastwood said in tribute to his friend.

I will remember him forever in The Conversation (1974), in which he plays Harry Caul, a surveillance expert caught up in a a murder intrigue in San Francisco. Harry is one of Hackman’s most recessive roles, or maybe the word is repressed. Francis Coppola coaxed the kind of performance for which Hackman was not noted - an internal and quiet dialogue with his conscience, in a film that was about taking responsibility for your work. This was sympathetic Hackman - a startlingly honest, exposed performance, with almost no shouting.

Hackman was for a long time the hardest working actor in Hollywood. He could do anything, from light comedy to tragedy, and he was never less than watchable in what he did. Was he the greatest of his generation? A lot of his peers thought so. It hardly matters whether you would prefer De Niro, Pacino, Hanks, Hoffman, Duvall or Nicholson - or indeed Hopkins, Heath Ledger or Ed Harris. We don’t have to choose. Hackman left us so much work to enjoy - and by those films, I will remember him. Fuck the headlines.

A very thoughtful article. Thanks for focussing exclusively on the quality of his work!

A fitting and appropriate riposte to, and reminder that, even if he wasn’t the headliner, he invariable stole the headlines, and sadly never more so than at the moment.

But his films will always testify to his greatness, which will long outlive this sad moment of attention on him, as opposed to his artistry.

Lovely piece, Paul!